This article is part of our CS101 series, designed for new coders and learners who want to intuitively understand the computer science theory behind the applications they use. In this post, we explore web servers — what they are, why they matter, and how they revolutionized software delivery.

Servers are everywhere—powering everything from the websites we browse, to the apps we use, and the data we rely on daily. They’re so deeply integrated into our lives that many of us intuitively know they are the backbone of our digital world. But how much do we really understand about the inner workings of these systems?

So, let’s take a step back and explore the roots of server technologies. Ready to dig in?

How Web Servers Changed the Game

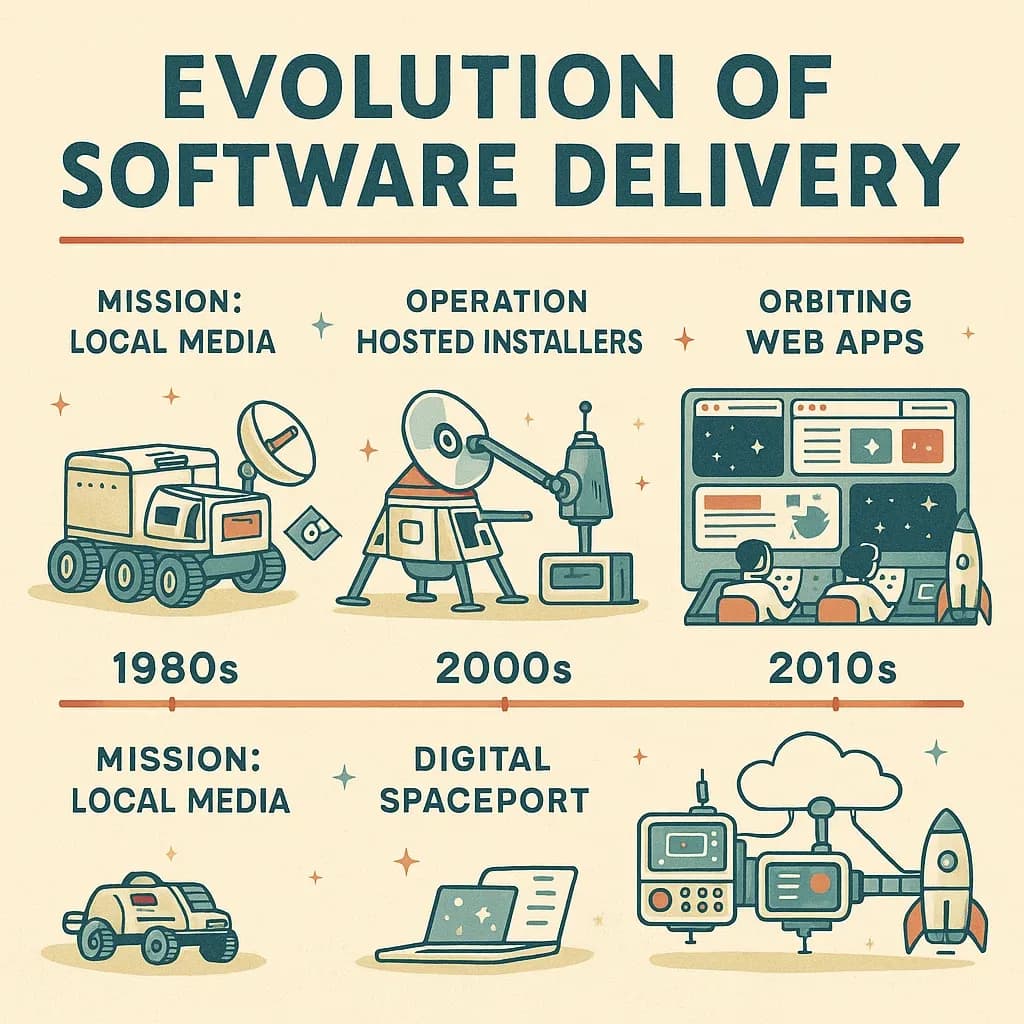

For years, software had been a tangible product — packaged in CDs or floppy disks, shipped off to users in boxes, and installed directly onto their machines. Whether it was a classic video game, office software, or early computer programs, one thing remained constant: the code ran client-side, meaning everything happened on the user’s machine. Software delivery was static, confined to what was contained in those hardware boxes, and updates or changes required entirely new shipments.

This world of static, local software was revolutionized in 1990 when Tim Berners-Lee ran the first web server at CERN. With the simple invention of the World Wide Web, we changed the landscape of how we think about software. For the first time, code could live elsewhere—on remote servers—allowing clients (in this case, web browsers) to send requests and retrieve fully functioning pages over the internet.

Here’s how it worked: a browser would send an IP address or domain name (DNS) request, and somewhere, through the magic of the internet, that request would land on a web server. The server’s job was to respond with the desired page, often generated dynamically on the fly. This was groundbreaking because, unlike client-side software that had to be installed on each machine, servers could now serve up-to-date content to countless users simultaneously, without being burdened by shipping or constant reinstallation.

The big deal about this was that software no longer had to live on your computer. Now, it could live on the web server, and anyone with a browser could just “request” what they needed from that server. This meant that the software could be updated or changed whenever the server wanted, and everyone using it would get the new version instantly—no more CDs or downloads needed. This was the birth of dynamic web applications, marking a shift in how we interact with software.

From Code to Cloud: Why We Needed Containers

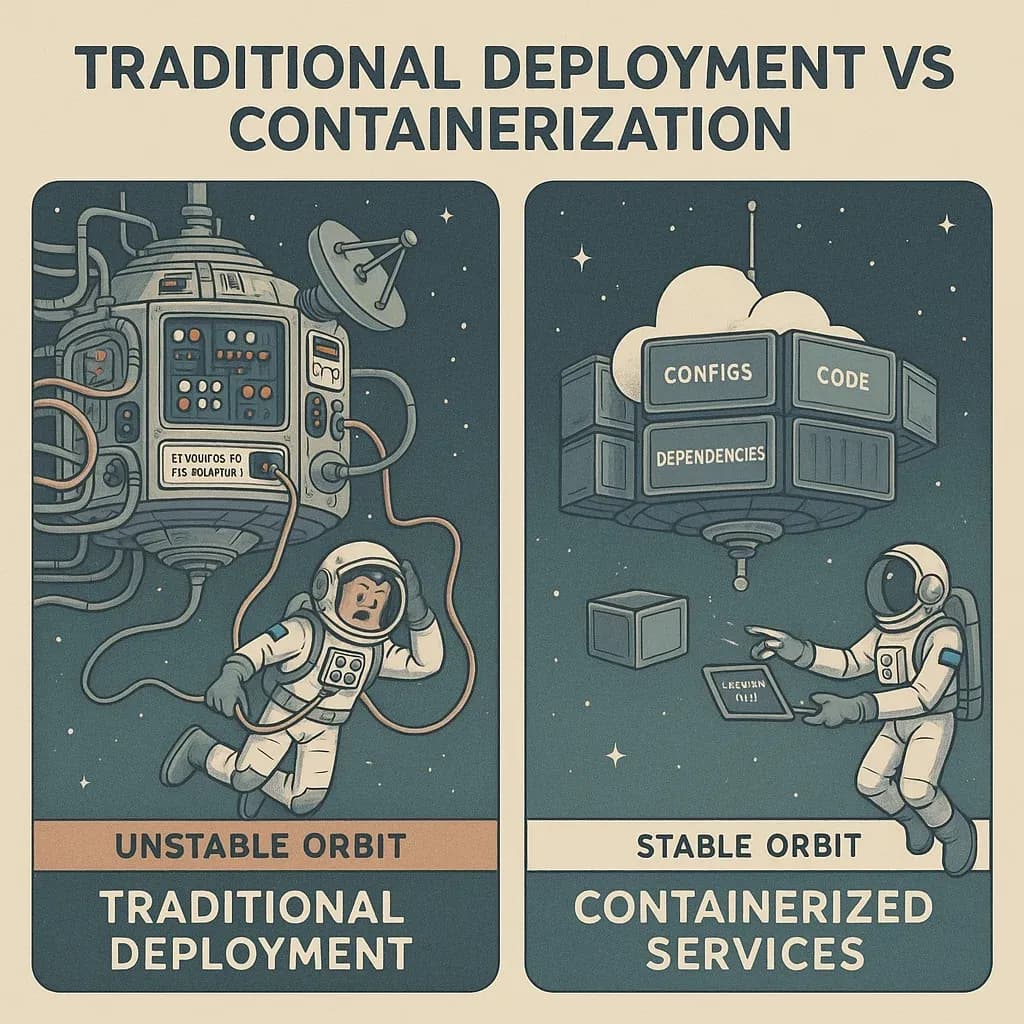

Once web servers made it possible to deliver software remotely, the next challenge was consistency. In the CD and floppy disk era, you shipped an entire, self-contained software package. But in the cloud era, apps were deployed to shared servers that needed to be configured just right—leading to the infamous “it works on my machine” problem. As software became more complex and global, deployment needed to be reliable, repeatable, and environment-agnostic.

That’s where containerization came in. With tools like Docker, developers began packaging not just their code, but everything it needed to run: dependencies, config files, and runtime environments. These containers could be spun up anywhere—from a laptop to a data center to the cloud—with guaranteed consistency. It was like shipping a CD again, but this time your entire server came bundled inside.

Putting Theory to Practice

Ready to go beyond theory? Our application for the tutorial today is inspired by a problem I faced as a CS student: there simply weren’t great tools to practice SQL outside of clunky setups like MS Access or OracleDB. To address this gap, we’ll be building a browser-based playground—something in the spirit of SQLBolt—that allows students to write, run, and learn SQL directly in the browser. This toy app will be our hands-on use case as we explore Docker, databases, and deployment. By the end of this tutorial, you’ll have a working prototype and a deeper understanding of how modern backend services come together.

Tutorial

In our TechLabs Berlin Summer 2023 workshop, we walked through the fundamentals of Docker and containerization—a must-have skill for modern backend, data, and infrastructure engineers. The workshop covered the basics of how containers work and why they matter, then jumped into a hands-on project deploying a toy application backed by a PostgreSQL database.

We also explored optional workflows for deploying apps to the cloud using platforms like Heroku, helping developers understand the lifecycle from development to production. This tutorial is perfect for anyone looking to gain confidence with cloud-native tools and see firsthand how abstract server concepts translate into real-world deployment. Whether you’re experimenting with containers for the first time or looking to expand your DevOps muscle, this guide is your launchpad.

Outro

From floppy disks to dynamic web apps, from static sites to containerized deployments—servers have shaped every era of digital innovation. Understanding how they evolved isn’t just trivia; it’s foundational knowledge for anyone looking to build modern, scalable applications. In this post, we traced that journey—from Tim Berners-Lee’s first server to deploying with Docker, Heroku, and PostgreSQL, and into the hands-on landscape of containerization

This isn’t just a story about the past or a toolkit for today—it’s a glimpse into the future of how software is built, served, and evolved. Whether you’re coding solo or collaborating on global projects, understanding the role of servers, containers, and modern deployment platforms will make you a more confident, capable, and creative technologist. Let these lessons guide your experiments, and let curiosity lead the way.